History of the flight

At 1523 h UTC on Tuesday July 11, 2017, flight NAX4287 operated by Norwegian Air Shuttle departed from Arlanda Airport, Stockholm, on a service to Helsinki. The captain was pilot flying.

The en-route portion of the flight was normal. The flight crew assessed the landing distance for the prevailing conditions and conducted a briefing on the essential aspects of the approach. The assessment of the landing distance was based on an ATIS message in effect for the aerodrome. The aircraft left the cruise altitude at 1546 h to commence an ILS approach to Helsinki-Vantaa airport. The initial approach to runway 04L was normal. Rain clouds were present in the area and winds were moderate.

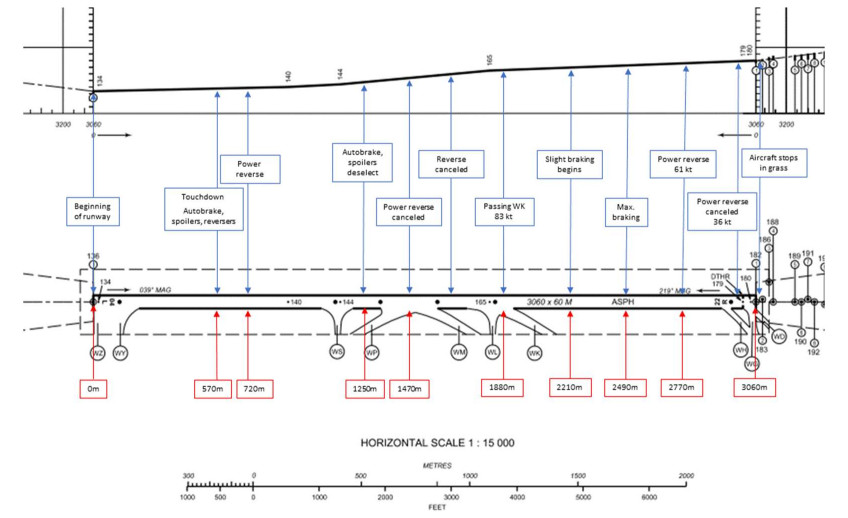

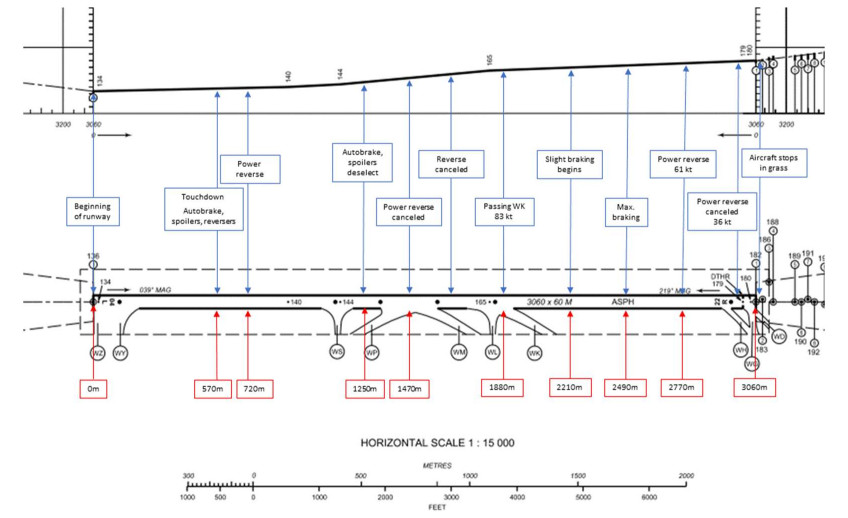

The touchdown was light and slightly beyond the optimum touchdown point at an airspeed that was almost right for the prevailing conditions. The captain selected reverse thrust at the moment of the touchdown, and reverse thrust became effective three seconds after the touchdown. The speedbrakes (spoilers) had been armed, but due to the light touchdown they did not deploy automatically. The captain deployed the spoilers manually one second after the touchdown. The autobrake system had also been armed and began to decelerate the aircraft normally upon spoiler deployment.

During the approach, the flight crew had planned to vacate the runway via high-speed turn-off WK. Due to the high speed, the captain elected to pass turn-off WK and vacate the runway via a taxiway at runway end. The captain canceled reverse thrust, and moments later also stowed the spoilers and deselected the autobrake system, which resulted in a marked reduction in the rate of deceleration. The captain applied light and full manual braking with approximately 850 and approximately 570 meters of runway remaining, respectively.

As the aircraft approached taxiway WH with approximately 300 m of runway remaining, the captain reselected reverse thrust and continued to apply heavy wheel braking. At this point, the aircraft was traveling at 64 kt (119 km/h). Because the captain had stowed the spoilers previously they did not deploy automatically. The captain attempted to steer the aircraft onto taxiway WD, which is the last taxiway at runway end. The captain canceled reverse thrust when the aircraft was traveling at approximately 25 kt (46 km/h), but due to excessive speed was unable to turn the aircraft onto the taxiway. The first officer called “brace” via the passenger address system.

The tires impacted the runway light fixtures by the time aircraft heading had diverged approximately 20 degrees from runway 04L heading. Both nosewheels and three mainwheels came to rest on the grass while the fourth mainwheel remained on the paved area.

The captain elected to not evacuate the aircraft. The air traffic control declared a local standby phase, and aerodrome rescue service units secured the aircraft. The aircraft was moved off the grass by a pushback tractor and towed to a position in front of the terminal building.

In accordance with regulations, airport maintenance units inspected the runway after the

incident. The runway remained closed for about one hour.

Figure 1 Graphic representation of the incident sequence. Distances are approximate and calculated from runway 04L threshold. (Basemap: ©ANS Finland Oy, overlays: SIAF)

There were no indications of fire and the captain did not order an evacuation. External steps were brought to the right front door of the aircraft. There were no injuries to the passengers or crew.

The aircraft was removed out from the soft area by towing it from the back using cables on both main landing gears; since the airport was not equipped with a tow bar. The aircraft moved to the parking area using its own power from engine No. 2 since engine No. 1 sustained damage on its fan blades due to ingestion of small gravels from the soft area.

Aircraft recorders (DFDR and CVR) were removed for the purpose of investigation.

1.3 CONSEQUENCES

The incident did not result in injuries to persons.

The aircraft and runway end lights sustained damage. Two runway light fixtures were toppled and damaged upon impact by the aircraft wheels. The wheels sustained damage upon impact with the metal mounting stakes of the light fixtures, and the fan blades of one engine received foreign object damage

1.7 METROLOGICAL INFORMATION

EFHK 111620Z 17012KT 5000 -SHRA FEW004 BKN009 BKN020CB 16/16 Q1004 BECMG 8000 BKN009 BKN020=

Runway 04L was wet from heavy rain. ATIS information indicated that 1 mm thick water patches were present on the runway. The flight crew estimated that the amount of water on

the runway was larger than indicated.

3.1 ANALYSIS

3.1.1 Departure from Stockholm and En-route Phase of Flight

The flight departed Stockholm 53 min behind schedule. It had already been delayed during

the departure from Helsinki, and the delay had since accumulated. Aircraft turnaround times

at airports are short. During the short time available, the passengers disembark and new ones

board, and the aircraft is fueled, loaded, and cleaned, and a delay in any one of these

operations may easily result in a late departure. Norwegian's manual states explicitly that the

goal is for 90 % of flights to be punctual within 15 minutes of the scheduled time since

punctuality is an element of good customer service. All airlines operate in a competitive

setting and have therefore set punctuality goals. Delays also incur additional costs to the

airlines.

Flight crew members generally find themselves in a problematic situation if flights are

frequently delayed for reasons beyond their control and feel pressed to minimize the delays

to the maximum possible extent. Short-duration flights, like the incident service from

Stockholm to Helsinki, allow the flight crew only limited possibilities to catch up with the

schedule. The captain used higher-than-normal airspeeds in accordance with the procedures

laid down in the company manuals. The delay had been reduced by a few minutes by the time

of landing at Helsinki.

Norwegian’s Organisation’s Management Manual (OMM) states that the company's two

operational priorities are safety and service. The aim of customer service is to offer low

prices, good service, and punctuality. A strive for punctuality or the minimizing of delays may

contradict with safety aspects.

3.1.2 Landing and Landing Roll at Helsinki

The touchdown was light and slightly beyond the normal touchdown point. Due to the light

touchdown, aircraft systems did not immediately detect a weight-on-wheels condition, and

the spoilers and autobrake system did not activate automatically. The captain had to deploy

the ground spoilers manually, which also resulted in simultaneous autobrake activation. The

braking systems activated after a slight delay, and due to the high speed the captain elected to

pass high-speed turn-off WK. It is recommended that medium jets such as the incident aircraft

vacate the runway via this particular turn-off. Having made this decision, the captain

deselected the braking systems to enable a more expeditious landing roll and to expedite

vacating the runway. At approximately 90 kt, the captain stowed the spoilers, canceled

reverse thrust, and deselected the autobrakes. Company manuals contain no standard

phraseology for the stowing of the spoilers and cancelation of reverse thrust during landing,

yet good airmanship presupposes that a flight crew member notifies the other flight crew

member of these actions. This maintains situational awareness of both crew members.

The company manual states that the computer software that flight crew members use to

assess landing distances is based on the spoilers and reverse thrust being in use until speed

has reduced to 60 kt.

The deselection of the braking systems resulted in a low rate of deceleration. Colored lights

positioned along the runway provide information on the remaining runway. The captain

initiated light braking at approximately 80 kt with 850 m of runway remaining. The captain

realized the situation too late and could not reduce speed sufficiently to turn the aircraft onto

a taxiway. He applied heavy braking when the aircraft was traveling at 74 kt and with 570 m

of runway remaining. Investigation showed that the airplane was not in a dynamic

aquaplaning condition during braking. Some viscous aquaplaning always occurs on a wet

runway.

The experienced captain was familiar with Helsinki-Vantaa airport. The flight crew was

satisfied with the expeditious landing until the aircraft was approaching the runway end. They

did not adequately anticipate and take into account the wet runway conditions. Water that

was present on the runway reduced friction and consequently the rate of deceleration during

the final phase of brake application. Since the captain had stowed the spoilers, the braking

distance was extended.

Deficiencies in flight crew communication during landing were noted. The captain did not

notify the first officer of the deselection of the braking systems, and the first officer did not

react to the captain’s actions. According to standard communication procedures, the first

officer shall only call out the deselection of the autobrake system, and the captain should

confirm manual braking in use. Good airmanship, good crew resource management, and good

situational awareness include the calling out of all actions that affect the flight. There was a

significant experience gap between the first officer and the captain. It should have been the

first officer's obligation to intervene when he noticed a hazardous situation developing, but he

remained confident in the captain's experience and aircraft handling skills. However, during

the final phase of the incident sequence the first officer notified, on own initiative, the cabin of

an impending impact.

Good airmanship presupposes, among other things, good crew resource management and that

all cockpit crew members maintain an awareness of the speed and position of the aircraft and

of the prevailing conditions. These requirements were not fully met on the incident flight.

3.1.3 Excursion

The captain continued full manual braking and reselected reverse thrust with approximately

350 m of runway remaining. Reverse thrust became effective after a delay due to the time

required for thrust reverser deployment and engine spool-up. The spoilers did not extend

automatically since the speed was below 60 kt at the moment reverse thrust became effective.

The flight crew could have extended the spoilers by operating the spoiler lever manually but

they did not do so.

The captain managed to steer the aircraft towards the taxiway; however, the turn was too

shallow and the aircraft departed the paved area. It came to a halt smoothly, and all occupants

remained uninjured.

The captain used the company's reporting system to file an occurrence report as required by

the applicable procedures. According to the guidelines of the company’s reporting system,

reporting is a legal requirement for the aircraft commander only. However, a voluntary report

may be filed by any employee who has observed any discrepancy, and in this incident the first

officer also filed a voluntary report. The company's occurrence reporting system is described

in the OM-A and OMM. The provisions contained in the latter are discussed here, since the

OMM is superior to the OM-A in the document hierarchy.

As a rule, the OMM encourages employees to report all events that an individual worker

subjectively assesses as reportable. Despite this, only mandatory reporting guidelines are

included in the manual, which explains that the aim is not to monitor day-to-day defects and

incidents since this would increase the workload for the reporters and the authorities and

might clog and obscure more significant safety items. On the other hand, the OMM mentions

root cause analysis and states that one of the safety aims is to identify the root causes of

accidents and serious incidents. This is contradictory to the concept of not encouraging

occurrence reporting. Recurrent anomalies, even though they may appear minor, may be

important indicators of root causes and a company safety culture.

The manual also describes a procedure for anonymous reporting, called ‘whistleblowing.’ Anonymous reports are submitted direct to the authority. However, the preferred method of

reporting is via the company’s SafetyNet reporting system.

3.1.4 General Airline Competition and Schedule Pressures

Competition and financial reasons have led airlines to set stringent schedule adherence goals.

Some flight schedules may even be unrealistic and turnaround times excessively short, which

deprives the employees of the possibility of achieving these goals. It is also probable that the

employees of companies engaged in the industry are aware of the fact that each lost minute

incurs additional costs to the company. Balancing in between the schedule adherence goals

and the safety goals may lead to the adoption of procedures that undermine safety.

Repeated delays and failures to attain the required punctuality frustrates the employees; if

allowed to continue, frustration will lead to negligence, which may manifest itself in noncompliance

with rules and procedures.

4 CONCLUSIONS 1. The flight departed Stockholm for Helsinki 53 min behind schedule. It had already been

late on arrival at Stockholm.

Conclusion: Competition and financial reasons, among other factors, have led

airlines to set punctuality goals. A strive for punctuality or the minimizing of delays

may contradict with safety aspects. If a punctuality goal cannot be met, attempts

will be made to minimize the delay since each lost minute incurs additional costs.

2. Since the airplane was traveling at a high speed, the captain elected to pass high-speed

turn-off WK. The flight crew aimed at vacating the runway via taxiway WD at the runway

end. The distance to this taxiway intersection was approximately 1,200 m. The captain

deselected the braking systems, and the aircraft continued down the runway at a speed

that was high in view of the prevailing conditions and position.

Conclusion: Due to the possibility of other traffic and punctuality goals set for

flights, flight crews attempt to vacate the runway as soon as possible.

3. Colored lights positioned along the runway provide information on the remaining runway.

The captain initiated heavy braking too late and could not reduce speed sufficiently to turn

the aircraft onto the taxiway. The captain did not anticipate the effects of the wet runway

and stowed spoilers on the braking distance.

Conclusion: Flight crew members must maintain situational awareness until the

very end of a flight.

4. Deficiencies in flight crew communication during the landing roll were noted.

Conclusion: Deficient communication may contribute to degraded situational

awareness.

5. Flight crew actions and crew resource management during the landing roll were not in

accordance with the company’s standard operating procedures.

Conclusion: Adherence to standard operating procedures is the cornerstone of safe

flying.

6. The first officer had been recently hired by the company. The first officer did not explicitly

indicate concern over the available runway. The first officer notified the cabin of an

impending impact on own initiative.

Conclusion: Employees recently hired by organizations may hesitate to intervene

in unexpected situations. Organizations should emphasize the importance of good

crew resource management during all phases of the flight.

7. Speed during the overrun was low, and the incident did not cause injuries to persons.

Conclusion: Runway excursions rarely have catastrophic consequences.

5 SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS

5.1 Requirements for Crew Resource Management Training

Good crew resource management (CRM) is an essential contributor to flight safety. Pilots’ basic training and recurrent CRM training emphasize, among other matters, the importance of

standardized communication and a preparedness to interfere with situations that are felt to

involve a potential safety hazard. Most serious incidents occur on runways and taxiways.

Investigation into this particular incident revealed a lack of appropriate CRM-related

communication between the flight crew members during the landing roll, which affected their

vigilance and situational awareness.

The Safety Investigation Authority recommends that:

EASA investigates how CRM training for ground operations can be enhanced.

[2018-S33]

5.2 Schedule Pressures

Competition and financial reasons have led airlines to set punctuality goals. Flight schedules

may even be unrealistic and turnaround times excessively short, which deprives the

employees of the possibility of achieving the punctuality goals. Recognized schedule pressures

may affect their work in a manner that degrades flight safety.

The Safety Investigation Authority recommends that

EASA investigates whether the current airline schedules are realistic or not, and also

determine their possible negative effects on the procedures of commercial aviation and

thence on flight safety. [2018-S34]

An earlier study (Eurocontrol, 2015) has shown that delays in commercial aviation are

increasing.

5.3 Implemented Safety Actions

EASA has published on its website safety material on CRM training implementation. In

addition, EASA has organized workshops on CRM-related matters for the responsible staff of

airlines and national aviation authorities. The workshops took place on November 1, 2016,

and August 29–30, 2017.

EASA has carried out a study on runway excursions. One aim of the study was to identify

means to improve regulatory action pertaining to runway safety, runway surface condition

assessment, and occurrence reporting.

EASA issued a document on runway surface condition reporting on January 18, 2018.

EASA investigates how CRM training for ground operations can be enhanced.

[2018-S33]

Read the full report here |

LN-NHF 737-800 Runway Overrun

LN-NHF 737-800 Runway Overrun