Synopsis

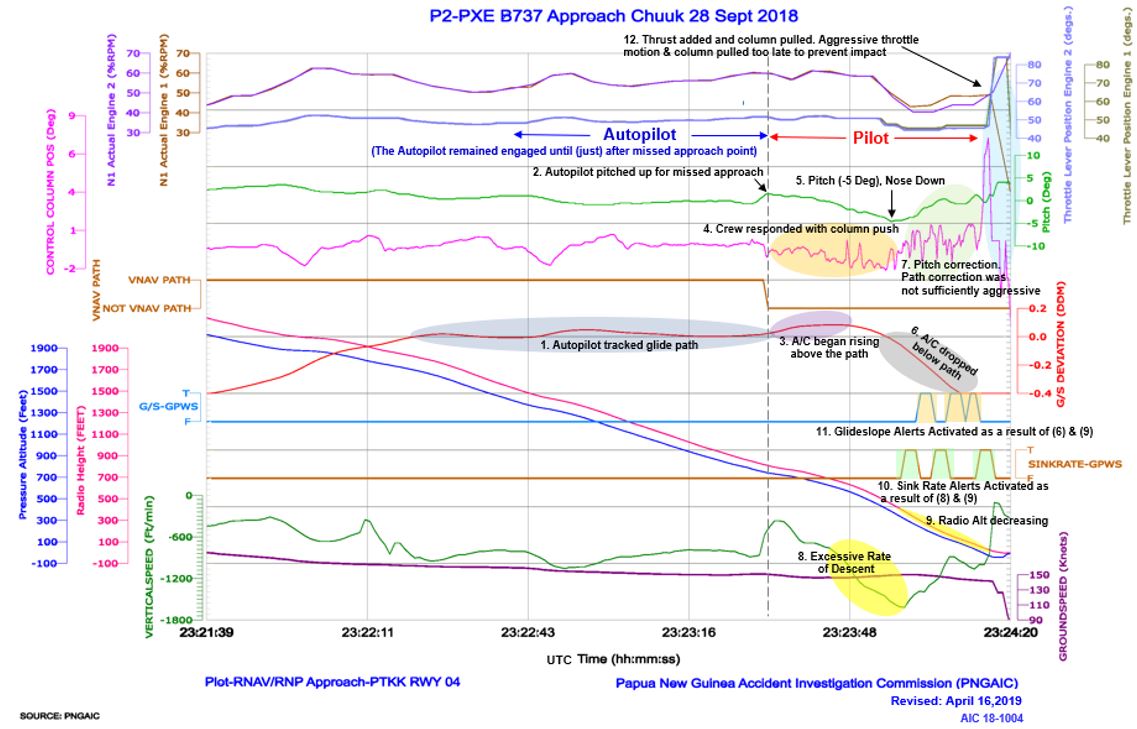

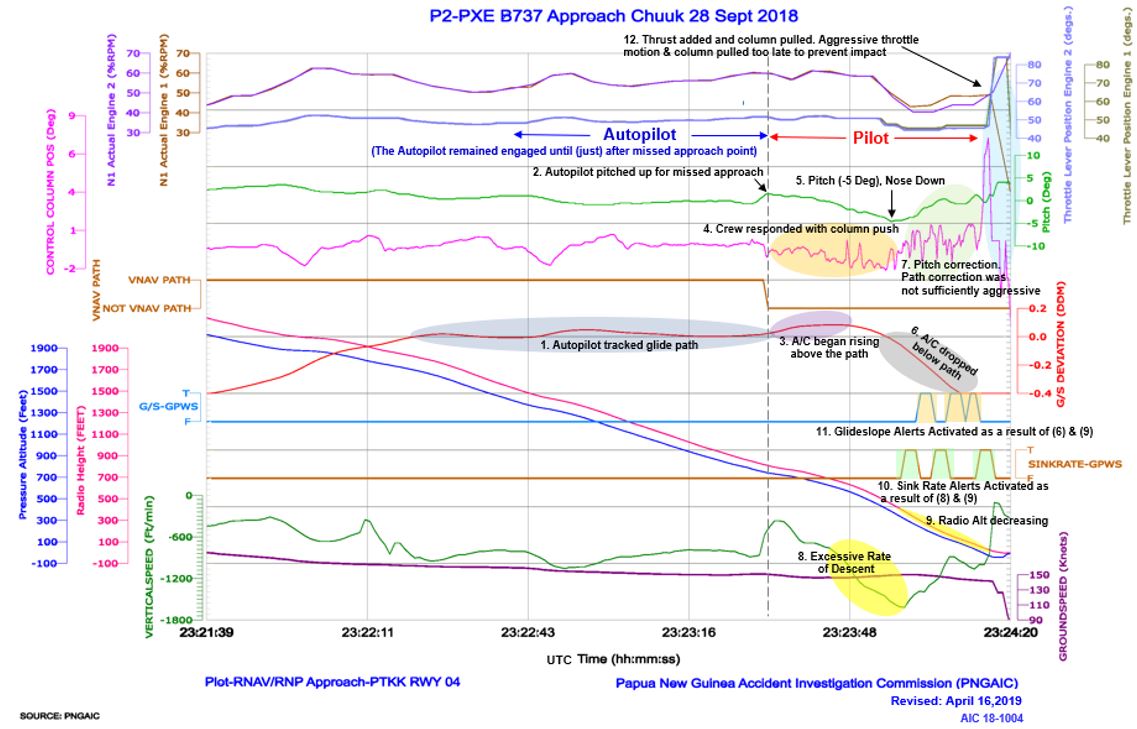

On 28 September 2018, at 23:24:19 UTC2 (09:24 local time), a Boeing 737-8BK aircraft, registered P2-PXE (PXE), operated by Air Niugini Limited, was on a scheduled passenger flight number PX073, from Pohnpei to Chuuk, in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) when, during its final approach, the aircraft impacted the water of the Chuuk Lagoon, about 1,500 ft (460 m) short of the runway 04 threshold. The aircraft deflected across the water several times before it settled in the water and turned clockwise through 210 deg and drifted 460 ft (140 m) south east of the runway 04 extended centreline, with the nose of the aircraft pointing about 265 deg. The pilot in command (PIC) was the pilot flying, and the copilot was the support/monitoring pilot. An Aircraft Maintenance Engineer3 occupied the cockpit jump seat. The engineer videoed the final approach on his iPhone, which predominantly showed the cockpit instruments. Local boaters rescued 28 passengers and two cabin crew from the left over-wing exits. Two cabin crew, the two pilots and the engineer were rescued by local boaters from the forward door 1L. One life raft was launched from the left aft over-wing exit by cabin crew CC5 with the assistance of a passenger. The US Navy divers rescued six passengers and four cabin crew and the Load Master from the right aft over-wing exit. All injured passengers were evacuated from the left over-wing exits. One passenger was fatally injured, and local divers located his body in the aircraft three days after the accident. The Government of the Federated States of Micronesia commenced the investigation and on 14th February 2019 delegated the whole of the investigation to the PNG Accident Investigation Commission. The investigation determined that the flight crew’s level of compliance with Air Niugini Standard Operating Procedures Manual (SOPM) was not at a standard that would promote safe aircraft operations. The PIC intended to conduct an RNAV GPS approach to runway 04 at Chuuk International Airport and briefed the copilot accordingly. The descent and approach were initially conducted in Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC), but from 546 ft (600 ft)4 the aircraft was flown in Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC). The flight crew did not adhere to Air Niugini SOPM and the approach and pre-landing checklists. The RNAV (GPS) Rwy 04 Approach chart procedure was not adequately briefed. The RNAV approach specified a flight path descent angle guide of 3º. The aircraft was flown at a high rate of descent and a steep variable flight path angle averaging 4.5º during the approach, with lateral over-controlling; the approach was unstabilised. The Flight Data Recorder (FDR) recorded a total of 17 Enhanced Ground Proximity Warning System (EGPWS) alerts, specifically eight “Sink Rate” and nine “Glideslope”. The recorded information from the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) showed that a total of 14 EGPWS aural alerts sounded after passing the Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA), between 307 ft (364 ft) and the impact point. A “100 ft” advisory was annunciated, in accordance with design standards, overriding5 one of the “Glideslope” aural alert. The other aural alerts were seven “Glideslope” and six “Sink Rate”. The investigation observed that the flight crew disregarded the alerts, and did not acknowledge the “minimums” and 100 ft alerts; a symptom of fixation and channelised attention. The crew were fixated on cues associated with the landing and control inputs due to the extension of 40° flap. Both pilots were not situationally aware and did not recognise the developing significant unsafe condition during the approach after passing the Missed Approach Point (MAP) when the aircraft entered a storm cell and heavy rain. The weather radar on the PIC’s Navigation Display showed a large red area indicating a storm cell immediately after the MAP, between the MAP and the runway.

The copilot as the support/monitoring pilot was ineffective and was oblivious to the rapidly unfolding unsafe situation. He did not recognise the significant unsafe condition and therefore did not realise the need to challenge the PIC and take control of the aircraft, as required by the Air Niugini SOPM6. The Air Niugini SOPM instructs a non-flying pilot to take control of the aircraft from the flying pilot, and restore a safe flight condition, when an unsafe condition continues to be uncorrected. The records showed that the copilot had been checked in the Simulator for EGPWS Alert (Terrain) however there was no evidence of simulator check sessions covering the vital actions and responses required to retrieve a perceived or real situation that might compromise the safe operation of the aircraft. Specifically sustained unstabilised approach below 1,000 ft amsl in IMC. The PIC did not conduct the missed approach at the MAP despite the criteria required for visually continuing the approach not being met, including visually acquiring the runway or the PAPI. The PIC did not conduct a go around after passing the MAP and subsequently the MDA although:

- The aircraft had entered IMC;

- the approach was unstable;

- the glideslope indicator on the Primary Flight Display (PFD) was showing a rapid glideslope deviation from a half-dot low to 2-dots high within 9 seconds after passing the MDA;

- the rate of descent high (more than 1,000 ft/min) and increasing;

- there were EGPWS Sink Rate and Glideslope aural alerts; and

- the EGPWS visual PULL UP warning message was displayed on the PFD.

The report highlights that deviations from recommended practice and SOPs are a potential hazard, particularly during the approach and landing phase of flight, and increase the risk of approach and landing accidents. It also highlights that crew coordination is less than effective if crew members do not work together as an integrated team. Support crew members have a duty and responsibility to ensure that the safety of a flight is not compromised by non-compliance with SOPs, standard phraseology and recommended practices. The investigation found that the Civil Aviation Safety Authority of PNG (CASA PNG) policy and procedures of accepting manuals rather than approving manuals, while in accordance with the Civil Aviation Rules requirements, placed a burden of responsibility on CASA PNG as the State Regulator to ensure accuracy and that safety standards are met. In accepting the Air Niugini manuals, CASA PNG did not meet the high standard of evidence-based assessment required for safety assurance, resulting in numerous deficiencies and errors in the Air Niugini Operational, Technical, and Safety manuals as noted in this report and the associated Safety Recommendations. The report includes a number of recommendations made by the AIC, with the intention of enhancing the safety of flight (See Part 4 of this report). It is important to note that none of the safety deficiencies brought to the attention of Air Niugini caused the accident. However, in accordance with Annex 13 Standards, identified safety deficiencies and concerns must be raised with the persons or organisations best placed to take safety action. Unless safety action is taken to address the identified safety deficiencies, death or injury might result in a future accident. The AIC notes that Air Niugini Limited took prompt action to address all safety deficiencies identified by the AIC in the 12 Safety Recommendations issued to Air Niugini, in an average time of 23 days. The quickest safety action being taken by Air Niugini was in 6 days. The AIC has closed all 12 Safety Recommendations issued to Air Niugini Limited. One safety concern prompting an AIC Safety Recommendation was issued to Honeywell Aerospace and the US FAA. The safety deficiency/concern that prompted this Safety Recommendation may have been a contributing factor in this accident. The PNG AIC is in continued discussion with the US NTSB, Honeywell, Boeing and US FAA. This recommendation is the subject of ongoing research and the AIC Recommendation will remain ACTIVE pending the results of that research.

Flight recorders

The aircraft was fitted with a solid-state cockpit voice recorder (SSCVR) and a separate solid-state flight data recorder (SSFDR). The SSCVR (P/N: 980-6022-001 & S/N:04448) and SSFDR (P/N: 980-4700-043 & S/N: 17869) were manufactured by Honeywell Aerospace. The CVR was installed at the rear fuselage of the aircraft. The SSFDR was installed in the ceiling at the rear of the passenger cabin.

The SSFDR was recovered from its rack within the aircraft by local civilian divers.

The SSFDR data revealed that during the approach from 1,000 ft amsl, with the auto-pilot engaged, the aircraft flight path was relatively constant and consistent with the RNAV profile. The rate of descent was around 600 to 800 ft/min and the groundspeed remained between 149 and 151 kts. The approach was stable.

After the auto-pilot was disengaged at 625 ft (677 ft), the aircraft’s descent rate increased from 750 ft/min and a groundspeed of 146 kts to 1,380 ft/min and a groundspeed of 149 kts, at 420 ft.

The FDR data showed an unstable approach from 625 ft (677 ft) and a flight path deviation from the 3º glideslope to an approach path profile averaging 4.5º.

Heavy rain and IMC were encountered at the minimums and the crew activated the windscreen wipers.

At 152 ft (189 ft) the rate of descent increased to 1,080 ft per min and the groundspeed was 147 kts.

At 121 ft (150 ft) with a ground speed of 146 kts, the rate of descent was 900 ft/min.

At 70 ft (100 ft) with a ground speed of 144 kts, the rate of descent was 1,080 ft/min.

At 53ft (84 ft) the rate of descent was 1,200 ft/min and the groundspeed was 143 kts.

At 30 ft (65 ft) and ground speed of 142 kts, the rate of descent was 1,290 ft per min.

From the first “Sink Rate” alert at 307 ft (364 ft) to the last “Sink Rate” alert before impact, there was also a red PULL UP warning displayed at the bottom of the PFD.

Note: The RNAV approach specified a descent rate of 743 ft/min at a ground speed of 140 kts to maintain a constant 3º descent angle (glideslope) to 50 ft over the threshold. The actual flight path (glideslope) flown from the point of glideslope deviation to impact gave an average angle43 of 4.5º.

The AIC produced a flight animation from the recorded data from the SSFDR, SSCVR, and EGPWS using the latest Flight Animation Software (FAS-INV). Refer to Chapter 5 – Appendices, Section 5.9, Appendix H.

SSCVR

The SSCVR was designed to record 30 minutes of audio on four channels (P/A, Co-pilot, Pilot, Cockpit Area Microphone/CAM) and 120 minutes of audio on 2 channels (combined crew audio & CAM).

Five days after the accident, at the request of the PNG AIC team, a Dukane Beacon receiver was brought from Guam by the US navy to locate the SSCVR. The SSCVR was recovered from the seabed by US Navy divers about 440 ft (135 m) back along the flight path from the 04 threshold, in the area ahead of the first point of water impact.

The SSCVR was downloaded and the data decompressed on 11 October 2018 at the PNG AIC Flight Recorder Laboratory in Port Moresby. The CVR captured 120 minutes of good quality recording from the PIC microphone, the copilot microphone and the cockpit microphone. The audio files were examined and the information was transcribed in the AIC Flight Recorder Laboratory.

Up to the time of the top of descent briefing, the oral communications between the PIC and the copilot and Air Traffic Control were in normal tones and in an orderly manner. Subsequently, during the approach below 10,000 ft, communication between the crew was minimal and was disjointed and not in accordance with standard operating procedures and standard phraseology.

The EGPWS sounded: ‘Sink Rate’ and ‘Glideslope’ alerts, continuously from shortly after passing the MDA until the aircraft impacted the water. There was a total of 13 loud EGPWS alerts (hard alerts) during the approach; six ‘Sink Rate’ and seven ‘Glideslope’ loud aural alerts. A 14th aural alert, ‘Glideslope’ registered on the FDR data, but was not heard on the CVR because it was over-ridden44 by the EGPWS “100 ft” call.

Significant excerpts taken from the CVR are as follows:

At the “approaching minimums” EGPWS call, the copilot said: “visual one red [pause] three whites”

From the EGPWS “minimums” call to the “100 ft” EGPWS call there were four “Sink Rate” warnings and five “Glideslope” warnings.

From the “100 ft” EGPWS call to impact with the water there were two “Glideslope” calls and two “Sink rate” calls. The pilots talked over many of the alerts until impact.

Until 2 seconds before impact, the copilot did not give the PIC any oral cautions throughout the approach despite the excessively high rate of descent and the aircraft increasingly being flown below the glideslope in an unstabilised manner and in IMC. As the pilot monitoring, the copilot did not challenge the PIC (the flying pilot) as required in the Air Niugini Limited Crew Resource Management (CRM) procedures.

Wreckage and impact information

The initial examination of video taken by the divers showed that the main landing gear separated from the aircraft during the water impact. The rear fuselage behind the wing had fractured during the impact sequence. The aircraft sank in 90 ft of water to the Chuuk Lagoon seabed.

2 ANALYSIS

2.3 Flight crew actions

During the flight, before the TOD briefing, the oral communications between the PIC, the copilot, and air traffic control were in a normal tones and in an orderly manner. However, during the approach below 10,000 feet, communication between the pilots was minimal and not in accordance with SOPs, and they were not using standard phraseology.

The PIC’s intention to continue the landing was reinforced when he asked the copilot to continue the landing checklist immediately prior to the EGPWS 1,000 ft annunciation. However, the CVR indicated that the only items covered were landing gear, flaps and lights.

The copilot did not provide effective monitoring and operational support to the PIC, and did not recognise the unstable approach. The evidence showed that he was unaware of the developing unsafe conditions. Due to his lack of situational awareness and vigilance, he was unable to recognise the need to correct the ever-increasing dangerous rate of descent below the glideslope.

At the minimums call, the copilot stated three whites with reference to the PAPI indicating high above the glidepath. The aircraft was not on the correct flight path and the rate of descent significantly exceeded 1,000 ft per min with the glideslope indicator indicating a rapid deviation from half dot low at the MDA, to two dots high within nine seconds after passing the MDA in IMC.

The crew were not complying with Air Niugini SOPs, and demonstrated that they were not situationally aware, and that their attention was channelised. Their actions indicated that they were fixated on a particular aspect and did not address the alerts and take corrective action. The PIC said that he found the Boeing 737-800 aircraft laterally less stable with flap 40 compared with flap 30 setting, resulting in lateral overcorrections of the aircraft after he disconnected the auto-pilot.

Both pilots stated during interview that they disregarded the constant Glideslope and Sink Rate aural alerts.

Video footage of the cockpit NAV display taken by the cockpit jump seat occupant showed an area of heavy rain on the approach in front of the aircraft immediately after the MAP. The missed approach track was outside the boundary of the storm cell and rain. However, the storm cell was between the aircraft and its intended landing runway.

If the crew had made the missed approach at the MAP, they would have avoided the heavy rain.

The investigation determined that when the aircraft entered the rain, all visual reference, if established earlier, would have been lost. The PIC informed the AIC that visual contact with the runway was lost in the final 30 seconds of the flight.

It is inconceivable that the PAPI or the runway were visible to either pilot as the aircraft was descending further below the glideslope in the rain. From 307 ft (364ft), the PFD displayed a red warning; PULL UP. That warning was generated by the EGPWS when the rate of descent exceeded a specified limit.

However, under the circumstances where the PIC’s attention was channelised, and the copilot was not effectively monitoring the displays and was lacking vigilance, that visual cue PULL UP was missed by both pilots. There was no aircraft generated aural hard warning to alert the crew to the approaching disaster.

There was ample information available to the flight crew from the EGPWS alerts and warnings to alert the pilots that the approach was unstable and therefore a hazard existed.

The Air Niugini SOPM Vol 11.3, section 12.7 stated that:

If a deviation exists at or below the stable approach gates (1,000 ft AGL in IMC or 500ft AGL in VMC) the PM shall make the relevant deviation call followed by the word “unstable”. The PIC shall announce “Go-around” and an immediate go-around procedure shall be conducted.

From the time the auto-pilot was disconnected at 625 ft (677 ft), the aircraft was never in a stabilised approach and so a go-around should have been conducted immediately.

The copilot was completely unaware of the hazardous situation unfolding and did not challenge the PIC and attempt to take control of the aircraft from the PIC and execute a go-around, in accordance with company instructions that require taking over when an unsafe condition exists.

The PIC’s actions were consistent with him being trapped in the condition called ‘fixated on one task’ or ‘one view of a situation even as evidence accumulates’. He intended to land the aircraft, and in doing so disregarded the alerts (EGPWS ‘Sink Rate and Glideslope’ indicating an unsafe conditon.

The approach to Chuuk was unstabilised and not conducted in accordance with Air Niugini SOPs.

2.3.1 Human Factors and medical

The AIC obtained the services of an aviation investigation medical practitioner who has specialised in aircraft accident and serious incident medical and psychological investigations for more than 20 years. Under the provisions of the Civil Aviation Act 2000 (as amended) and the Commissions of Inquiry Act, this expert examined ALL relevant evidence and provided the AIC with assessment and findings. No evidence of fatigue was presented.

Inattention, or decreased vigilance has been a contributor to operational errors, incidents, and accidents worldwide. Decreased vigilance manifests itself in several ways, which can be referred to as hazardous states of awareness.

These include:

1. Absorption. A state of being so focused on a specific task that other tasks are disregarded.

2. Fixation: A state of being locked onto one task, or one view of a situation, even as evidence accumulates that attention is necessary elsewhere, or that the particular view is incorrect.

3. Channelised attention: A mental state which exists when a person’s full attention is focused on one stimulus to the exclusion of all others. This becomes a problem when the person fails to perform a task or process information of a higher priority and thus fails to notice or has no time to respond to cues requiring immediate attention.

4. Fascination: An attention anomaly in which a person observes environmental cues, but fails to respond to them.

5. The ‘tunnelling or channelizing’ that can occur during stressful situations, which is an example of fixation.

Note: The term ‘fixation’ has been chosen to describe the PIC’s state of alertness, which provides a clearer idea of ‘being locked onto one task’, than ‘absorption’. Several ‘findings’ support this ‘tunneling or channelized’ condition, for example:

• The PIC’s attention became fixated on landing the aircraft.

• The crew did not respond to 13 EGPWS aural caution alerts and the PULL UP visual warning. The PIC did not change his plan to land the aircraft, although the aircraft was in unstabilised condition. The other tasks that needed the crew’s attention were either not heard or disregarded. The auditory information about other important and hazardous things did not reach their conscious awareness.

• The PIC flew an unstabilised approach. The PIC’s intention to continue to land the aircraft, from an excessively high rate of descent when in IMC and below the minimum descent altitude, was a sign that his attention was channelized during a stressful time.

• The PIC’s decision to continue in IMC past the MAP and not conduct the missed approach was flawed. In choosing the landing option rather than the go around the PIC fixated on a dangerous option.

2.4 Enhanced Ground Proximity Warning System (EGPWS)

The investigation found that the crew did not take any remedial action in response to the Glideslope and Sink Rate Caution64 alerts (aural alerts). The EGPWS additionally issued the red PULL UP visual alert on the PFD at 307 ft (364 ft) when the aircraft penetrated the Sink Rate Envelope of the Honeywell EGPWS MK V Mode 1 Graph. (See Figure 32). During the approach the crew lost situational awareness, with their attention channelised, and the aircraft entered the storm cell with heavy rain after passing the MAP. The PIC did not arrest the excessive rate of descent, and flew the aircraft increasingly below the Glideslope. The crew of P2-PXE were fixated on the task of landing the aircraft and did not notice the visual PULL UP caution alert at the bottom of their PFD. Therefore, they (crew) did not take any positive action to arrest the high rate of descent and avoid landing in the lagoon. In fact, neither of the pilots were aware of the rapidly unfolding unsafe situation. The investigation found that the crew had received similar aural alerts on previous approaches in visual conditions where the aircraft was safely landed. This would have contributed to the perception that the alerts during the accident approach were nuisance alerts, and therefore disregarded them. A visual display of the steady red PULL UP on the PFD, was not noticed by either of the pilots, and therefore was not sufficient to alert them to the imminent danger. A steady message surrounded by lights during a critical phase of flight where the PIC is fixated on other displays may not be an effective means of alerting the crew that the unsafe situation has developed to the next level. The investigation determined that the light blended in with the displays and was not noticed by both pilots when it illuminated, nor did it have any features to effectively draw the attention of the crew after its illumination. The AIC Human Factors investigation determined that it is likely that a hard aural ‘WARNING’ alert or a flashing visual PULL UP would have more effectively drawn the attention of the pilots during this critical phase of flight where workload was higher and attention fixated. It could be the last line of defence for any crew who may unknowingly or inadvertently get in a similar fixated situation. The investigation found that it is important for aircraft alerting systems to be able to effectively draw attention and provide information to flight crew, to allow them (the crew), to distinguish between levels of unsafe situations as they develop. If an alert signifying an elevation of an unsafe condition is missed by crews, they may not be able to recognise that the unsafe condition has developed to the next level and requires urgent corrective action. In January 2019, the AIC recommended to Honeywell that a continuous “WHOOP WHOOP PULL UP” hard aural warning, simultaneously with the visual display of PULL UP on the Primary Flight Display, should replace the Sink Rate Caution alerts (aural alerts) to alert a crew of imminent danger when the aircraft continues to descend below 500 ft Radio Altitude and below the glideslope. However, during subsequent discussions with Honeywell and Boeing, the AIC was informed that such hard-aural warning might not be an option for older generation EGPWS. From a Human Factors perspective, in the absence of a continuous “WHOOP WHOOP PULL UP” hard aural warning, changing the steady PULL UP visual display to a flashing visual display PULL UP on the PFD is desirable. That could be more effective than a steady PULL UP visual display to alert flight crews to imminent danger when the aircraft continues to descend below 500 ft Radio Altitude and below the glideslope. A hard-aural warning alert or flashing visual warning, demanding an immediate flight crew response would clearly be desirable in the interest of safety enhancement. The AIC issued recommendations to Ho n Administration in relation to EGPWS alerts and warnings.

Causes

- The flight crew did not comply with Air Niugini Standard Operating Procedures Manual (SOPM) and the approach and pre-landing checklists. The RNAV (GPS) Rwy 04 Approach chart procedure was not adequately briefed.

- The aircraft’s flight path became unstable with lateral over-controlling commencing shortly after auto-pilot disconnect at 625 ft (677 ft). From 546 ft (600 ft) the aircraft was flown in Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC) and the rate of descent significantly exceeded 1,000 feet/min in Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC) from 420 ft (477 ft).

- The flight crew heard, but disregarded, 13 EGPWS aural alerts (Glideslope and Sink Rate), and flew a 4.5º average flight path (glideslope).

- The pilots lost situational awareness and their attention was channelised or fixated on completing the landing.

- The PIC did not execute the missed approach at the MAP despite: PAPI showing 3 whites just before entering IMC; the unstabilised approach; the glideslope indicator on the PFD showing a rapid glideslope deviation from half-dot low to 2-dots high within 9 seconds after passing the MDA; the excessive rate of descent; the EGPWS aural alerts: and the EGPWS visual PULL UP warning on the PFD.

- The copilot (support/monitoring pilot) was ineffective and was oblivious to the rapidly unfolding unsafe situation.

- It is likely that a continuous “WHOOP WHOOP PULL UP” hard aural warning, simultaneously with the visual display of PULL UP on the PFD (desirably a flashing visual display PULL UP on the PFD), could have been effective in alerting the crew of the imminent danger, prompting a pull up and execution of a missed approach, that may have prevented the accident.

US NTSB STATE OF MANUFACTURE CONCLUSIONS

The US National Transportation Safety Board’s Accredited Representative and Technical Advisers representing the State of Manufacture, had full access to the evidence, including all recorded data and the cockpit imagery (video), in accordance with Annex 13 international obligations. The NTSB team provided their conclusions, which have been duly considered during the drafting of the Final Report.

With respect to cause #7 above, the NTSB Team requested that the substance of their comments be appended to the Final Report, in accordance with Paragraph 6.3 of Annex 13, Standard.

The AIC agreed to publish the NTSB Team’s findings and conclusion, which states:

NTSB staff disagrees that an additional warning would have been effective in alerting the crew. The conclusions and the supporting information in the draft report effectively demonstrate that the pilots:

• Lost situational awareness. • Disregarded 16 EGPWS alerts that had occurred in the 19 seconds preceding impact with the water. • Disregarded vertical guidance being displayed on the Primary Flight Display (PFD). • Did not comply with the Air Niugini go-around policy after the first and subsequent EGPWS alerts. • Did not comply with the Air Niugini go-around policy after the approach had become unstable with the descent rate exceeding 1000 feet per minute.

NTSB staff believes that the actions of the pilots to disregard the 16 EGPWS alerts and to not comply with Air Niugini policy clearly demonstrate that the crew was unresponsive to guidance that should have prompted a clear and decisive action to initiate a missed approach.

NTSB staff believes the disregard of the alerts, disregard of the PFD display guidance, and the continuation of an unstable approach demonstrate that any additional guidance, alert, or warning would be similarly disregarded by the flight crew and ineffective in preventing the accident.

A preliminary report was issued giving some factual information but all analysis and conclusions were reserved for the final report which was published 19 Jul 2019. |

|

P2-PXE 737-800 Landed short of runway

P2-PXE 737-800 Landed short of runway